Steve Dillon 1962 - 2016

Originally published on The Abadzone Tumblr, November 2016

When I heard the news about Steve Dillon, I’d seen him only very recently. He was happy and positive then, and he looked brilliant. After a long illness that had seen a turnaround, he was on the up. There was cause for hope.

I held back from making a detailed online tribute to him straight away because that really was a terrible week and I wanted to gather my thoughts. The day before, my wife and I learned of a death in our own family, and then finding out about Steve the following day was like the second of a one-two punch, the first of which had already knocked us senseless. Trips abroad and parenting arrangements had suddenly to be rearranged, and then came November, which brought its own uniquely ill wind, and not just for us. The world felt more sullen and cold.

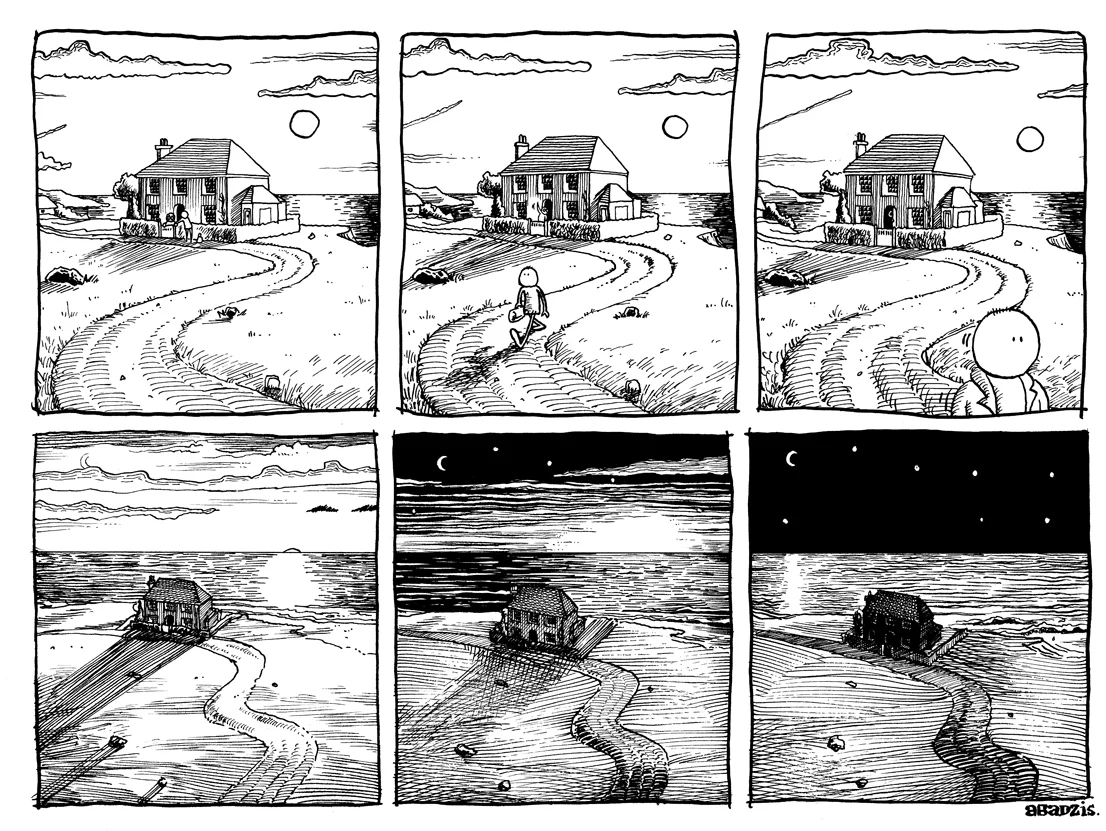

I spent the early part of the month attending a book festival in the Outer Hebrides, the Western Isles of Scotland. It’s a wild and some would say bleak place, warmed by the people you find there.

Approaching by air, it feels as if you chance upon it, a rising, mossy, carpeted stone scored through with silver lochs, all framed in tumbling iron caterpillars of surf. It’s cold but most certainly not sullen, with monumental grey and yellow skies. On the ground, the landscape seems to brace itself between ocean and heavens, extending forever in all directions as it pulls tides back and forth across the memory.

I thought a lot about Steve and wrote most of this while I was there. Steve was a big part of my personal mythology, although if I’d have ever told him that, he would’ve fixed me with a questioning look and waved it away. Any time you try and plot a path of creativity backwards, it feels vaguely unnatural, as if you’re trying to impose an unreal order on a chaotic process that will always resist ever being precisely mapped. But this is how I remember things.

After Steve died, the Internet was full of tributes to his mainstream work, and rightly so – his copious and influential output with our mutual friend Garth Ennis includes not only Preacher but numerous Marvel and DC/Vertigo properties like Punisher and Hellblazer. Way back when, he was a major early contributor to 2000AD and was, to my mind, one of the early definitive artists on Judge Dredd. 2000AD is where I first encountered his work – there, Warrior magazine and in the back pages of Doctor Who Weekly (as it was, back then). I mention his Doctor Who work as it was a big early influence on me, and there’s a pleasing circularity to it because, along with the fact that I’ve written many Doctor Who comics, it was also Steve who gave me my first big break in the industry as a storyteller.

Doctor Who in the comic strip medium has a history almost as long as the show itself, but Steve’s strips were filmic in scope before the show ever had the budget to do similar. Steve took the ethos he brought to his Judge Dredd strips and fused it with the imaginative universe of the BBC’s time traveller, creating characters and back-up strips that were wider and deeper than anything yet seen onscreen. Even as a child, I knew his stuff was a cut above the norm.

This, I suppose, before I’d ever even met him, was his first lesson – tell the story well, with clarity and precision. Although his drawing style was never flashy for the sake of it, it was always dynamic, vividly cinematic in its power, even if a scene was just a couple of characters having a conversation. Steve could make the seemingly mundane sing. He could shift from a pair of talking heads to fast-paced high drama within the guttering of two panels, and never lose the immersive sense of a story.

In late 1988, Steve Dillon and Brett Ewins co-created Deadline magazine, a comics and music rag that changed British comics. Its cultural impact was far wider than anyone who worked on it suspected it would be, least of all me. The idea was that Deadline would provide something different to the other comics that were around. It would be a forum for young comics creators and allow them to own their own characters. Very quickly, its remit expanded to include all kinds of fantastical and zeitgeisty contributions, which really just reflected its editors’ tastes.

Although there were good comics around, the mainstream ones were aimed at kids and beholden to genres, like the groundbreaking but mostly SF-orientated 2000AD or the other war and action titles – “boy’s comics” – that Fleetway produced or the funnies from DC Thomson aimed at a younger age group. There were a few alternative indie titles like the excellent Escape, Inkling or the Fast Fiction crowd (from whence cartoonists like the great Eddie Campbell, Glenn Dakin and Ilya emerged), but Deadline was neither as arty nor sophisticated as these.

Deadline was something more anarchic than either mainstream or indie comics of the time, something more like music in the sense that it was possessed of a more direct pop culture influence and awareness, a brand new DIY kitchen-sink mentality that put two fingers up at the status quo. Also, girls were invited - they were welcome to read, contribute and indeed even turn up as fully rounded characters in the strips themselves. (Sometimes.) In an industry that, up until that point, had been largely divided along gender lines, this was fairly progressive. Because it was distributed by WH Smith, getting the likes of Rachael Ball, Carol Swain and Julie Hollings onto the shelves with some regularity where both male and female readers could discover them was actually a big deal.

None of this was adherence to a strict policy of course, this was just Steve and Brett being open-minded and generous, and not wanting to tow the line and do things the way they’d found them done elsewhere. Sometimes, especially when I met other contributors at one of the parties Deadline hosted, I felt like we were all in a vast shambolic band. Members would come and go, each one contributing their own solo or muscular riff that would influence somebody else to take the cacophony in another new direction, another new raucous inflection of comics. It was raw, expressive creativity unleashed, unshackled by the requirements of the mainstream.

For my own part, I got involved in the mag thanks to the stroke of luck of renting a small studio in the space next door to Deadline just as they were starting up. When I found out who the neighbours were, I stuck my head over the partition that divided us and asked if they’d look at my portfolio. I can still recall their amusement at the cheek of that, the welcoming glow of their enthusiasm and energy.

It was Brett who found an unnamed stickman character lurking at the back of my art samples. He stopped flicking through them, pulled a page out and said, “This is different,“ and handed it to Steve, who read it and nodded in approval. "Yeah, we’ll have this.” And it was Steve, after that point, who really became my storytelling mentor.

I was not a confident artist in those days, and my stickman, who gained the name Hugo Tate with Steve’s blessing, would appear alongside art and stories by the likes of D'Israeli, Jamie Hewlett, Philip Bond and Steve’s younger brother, Glyn. These guys could really draw, while I’d invented Hugo as a means to prevent myself stressing over my own perceived lack of ability. Steve encouraged the looseness of my drawing, and told me to focus on my strengths. "You’re a good writer,” he said. “Write, and just let the drawings be expressive. That’s what you do.” That might be the best piece of advice anyone ever gave me.

I used to time delivery of my pages of art to Deadline HQ deliberately late to see if Steve would be up for a pint, possibly with Brett, or Ra Kahn, Chris Rudolf, Tom Frame or whoever else happened to be in the office. Steve was only a few years older than me, but he’d been working in comics for years already. He was, improbably, already an industry veteran. He knew stuff. Plus, he was a laugh and he liked my ideas of “what comics could be.“

The drawings remained expressive, but with Steve’s continued input, my confidence grew. He never "edited” exactly, but he’d give advice and suggest directions, identify strengths. He noticed that the character of Hugo himself was becoming a metaphor, unrefined and inked with a raw quality while everything else around him was growing more figurative and highly rendered. He encouraged the use of that metaphor, a Tintin-esque tabula rasa or Charlie Brown-alike. As a strip, Hugo Tate evolved from single, one-off-episodes into a longer story, a rites-of-passage tale where I could flex my desire to write more complex characters in less familiar locales. It’s possible I’d never have developed that storytelling muscle, that particular instinct for layered drama, had it not been for Steve and Brett’s indulgence, and Steve in particular giving me the support and latitude to do so. He often made sure I had the space to experiment, and extra if I needed it.

Steve co-edited Deadline with Brett for only about a year-and-a-half, certainly less than two, after which he moved to Dublin. He still contributed strips, but a short time later when Brett handed over editorial duties to Dave Elliott, it became clear neither would be returning.

Steve moved back into mainstream comics and, eventually, into some major collaborations with Garth Ennis, including Preacher, an era of his career that might be better documented. His time on Deadline was brief, but it was incredibly influential. For all its chaos, the magazine was a fertile hotbed of creativity, all facilitated and encouraged by these two benign, incredibly imaginative nutters. Both Steve Dillon and Brett Ewins are now gone and I feel that, in many ways, they were never fully recognised for their contributions to British comics culture. But then, I’m not sure Britain fully recognises its own comics culture, even now, which is why many of its best and most talented practitioners end up seeking work abroad or in other creative fields.

Many years later, sitting in a bar in New York City with Garth, I teased Steve that he was my “comics dad,” even though we’d long closed that age gap. He rolled his eyes at that, because he was a humble sort of bloke, not great at taking compliments, and could never take credit for encouraging my blossoming talents and storytelling experiments. That, however, is precisely what he did. Steve was crucial at that time, and without him, I don’t think I’d have developed into the kind of artist or writer that I came to be. It’s fair to say that, without Steve Dillon’s influence, I would not be doing what I’m doing today.

He didn’t just do it for me. In addition to roping in friends and colleagues like Pete Milligan and Brendan McCarthy, with Deadline Steve and Brett created room for many other comics creators, including Glenn Dakin, Rachael Ball, Matt Brooker (AKA D’Israeli), Ed Bagwell (AKA Perryman), Alan Cowsill, John McCrea. He did it for his brother Glyn, he did it for Jamie Hewlett, Alan Martin, Philip Bond, Jon Beeston, Andy Roberts, Shaky Kane, Carol Swain, Ilya (AKA Ed Hillyer), the Pleece Brothers, William Potter and many, many others.

Steve…? Cheers, mate.